Liquidation models are a tool that business owners and investors alike can use to evaluate a company’s capitalization structure in preparation for raising capital from investors, comparing investment opportunities, and incentivizing employees. In this series of articles we will discuss some of the important considerations in constructing liquidation models.

There are a large array of possible models to utilize from high-level simplistic excel models to very detailed models (or just the stock ledger itself) usually managed by cap table software such as Shareworks or Carta. So we will cover them like this:

In Part A, we go through the basics of a top-down excel model. In Part B, we will talk about some nuances of modeling recursive complexity in a top-down excel model. And in Part C we will talk about the pros and cons of switching to a bottoms-up model using linear interpolation to fill in the gaps between data points.

To start with, we should make it clear that a liquidation model (aka shareholder waterfall analysis) is not really the same as a cap table model is not the same as a stock ledger. They can share a lot of the same characteristics and data points, and can even be interlinked or layered to form a very holistic picture of reality, or plan for specific future scenarios. But the requirements of a model, and its “correctness” will change over time as a business moves from a concept, to formation, to operation, to exit. So before you decide which you need, it’s important to ask what you are trying to decide or accomplish and who your audience is.

Let’s jump into a simple excel model (example available in Downloads – File: Liq_Model_PartA_v1.xlsx).

Fundraising Synopsis: In this example, the company took no angel investment – let’s call it self-funded. They started with a simple equity structure for founders, treasury and early employees consisting of 7.5M shares of Common Stock.

They sold 25% of the company in a Series A fundraising for $5M, issuing 2.5M shares of preferred stock @ $2.00 per share at a post-money valuation of $20M, with an agreement to create a post-money options pool of 2.5M (potentially 20% of fully diluted ownership). So Series A preferred shareholders would have no less than 20% on a fully diluted basis.

Two years later they raised a $15M Series B, issuing 2.5M shares of preferred stock @ $6.00 per share at a post-money valuation of $90M for 16.7% of the company. And two years after that they raised $60M, issuing 3M shares @ $20 per share at a post-money valuation of $360M for 16.7% of the company. Along the way they also picked up two term loans for $20M total. By the way, this example assumes that all preferred shares are non-participating with a 1x liquidation preference.

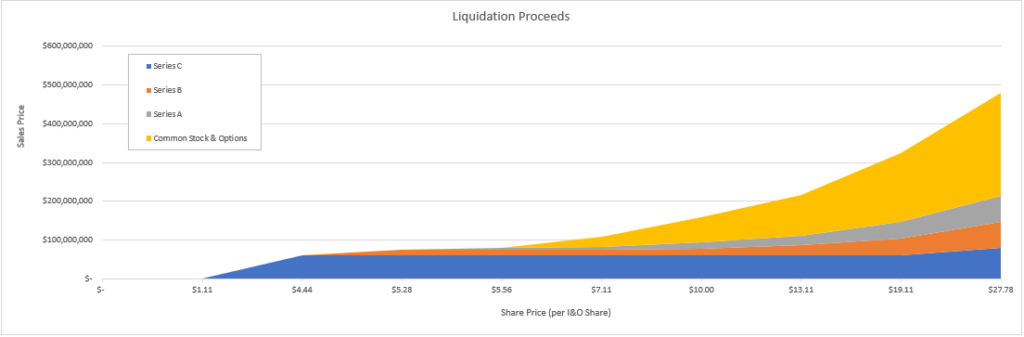

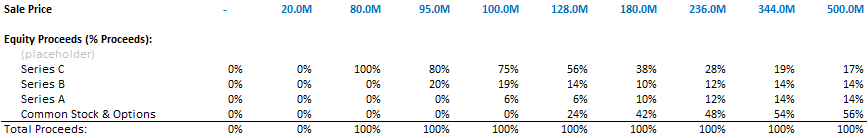

The Model Itself: At first glance this model looks great. Without getting into details, it takes into account liquidation preference correctly and provides a good breakdown of equity proceeds at various exit values, which is what it’s supposed to do. It even has a nice graph (Figure A)!

However, in reality this model is only good enough for planning purposes, maybe early on in a company’s development or conception to mock up rough funding scenarios. Or for an investor laying out future capital needs vs their fund timings. Why is that?

Let’s go through its “correctness”:

The good:

- Handles liquidation preference and general waterfall analysis of equity proceeds at various exit valuations

- Provides a distinction between what’s listed in the stock ledger vs what you want to model, for scenarios like vested vs unvested options

- Provides a flexible enough structure to add or remove rounds or some deal terms for analysis and discussion purposes

The bad:

- Dependency flow works off of simple per share value (sale price per share)

- Modeling logic and flow are linear; can not handle any contingent logic for things like convertible notes or layers of options with varying strike prices.

- Modeling logic lives in the same place as output, making presenting this information a bit difficult

The ugly:

- Does not take into account Options strike price or employee vesting

- Treats Common and Common Options as one block in calculating equity proceeds (Figure B)

- Debt is treated as a simple balance with no repayment schedule or interest considered

So if you were working inside a company or investing in a company after they had raised this amount of capital, you would have much more detail available and likely need your model to be more “correct”. Since at that stage you might need to fine tune or right size an employee options pool, or refinance credit facilities. Both of which would require a more mathematically correct model of the situation, incorporating details of things that have already happened in the past.

But if you’re a founder or investor working with early stage founders a model of this basic level can be a great way to mock up a funding path, or create a good foundation for employee compensation discussions. Because there are so many future unknowns at that point, it’s probably better to keep it simple, and focus on the decision process vs the “correctness” of the model.

Let us know what you think of this concept of model “correctness” over time or things you may have done differently below.